A load of balls

Contrary to popular belief, Dutch Balls is not the title of a 1970s porn movie (actually it might be, I haven’t dared check). Instead, it’s a commonly used translation on…

Contrary to popular belief, Dutch Balls is not the title of a 1970s porn movie (actually it might be, I haven’t dared check). Instead, it’s a commonly used translation on English menus for that most ubiquitous of Netherlandish bar snacks: bitterballen. But what are these oddities, and from whence did they come?

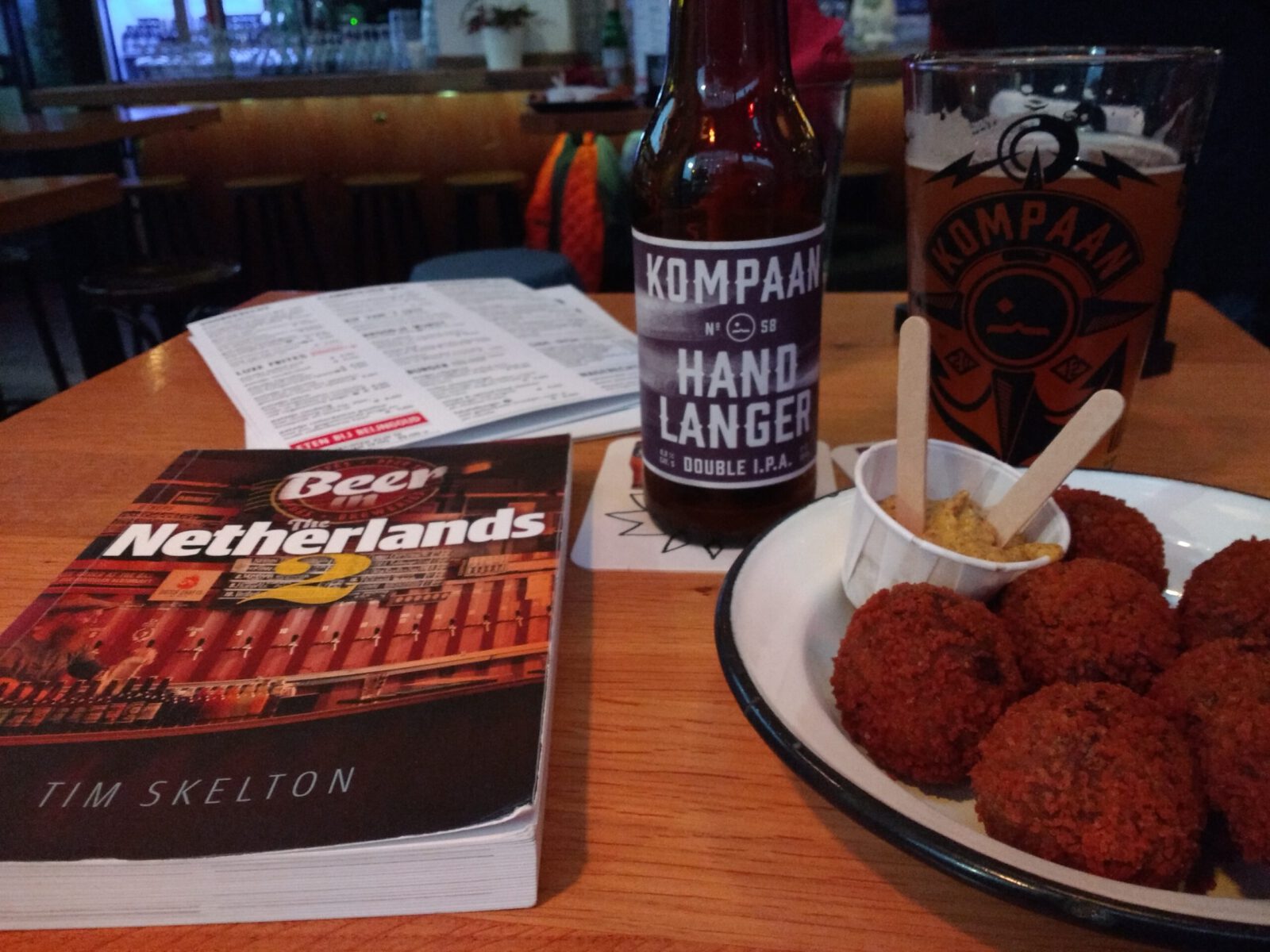

Put simply, bitterballen are breaded, deep-fried balls containing a flour-thickened ragout of (traditionally) beef, although there are now variations with every filling imaginable. It’s not exactly a meatball as the centre is intentionally sloppy. More of a savoury praline. With no chocolate. Moreover, the quality of the meat (or meat alternative) is often masked by the roux sauce, which is why there are some sceptics when it comes to claiming their place in the Dutch culinary hierarchy.

Some say bitterballen’s origins lie some 2,000 years before the actual bar snack came into existence. It is believed that the Batavian tribes who lived in the area now called Gelderland mixed leftover ox meat with fat and bread to make a stew thick enough to cart around as a packed lunch on hunting trips. Legend also has it that the invading Romans later adopted the dish, and the recipes were passed down through generations and centuries, becoming beef-centric when the local ox population died out.

Whether that has any direct link to bitterballen is a matter for conjecture, particularly as the next link in the chain didn’t happen until the 1560s. When the Eighty Years’ War broke out in the Spanish Netherlands, the occupying Habsburg forces suddenly found their supplies of imported chorizo and olives hard to source. In order to satisfy their Iberian tapas cravings they took to rolling the local beef ragout in egg and breadcrumbs and frying it, creating a recognisable croquette. Allegedly. And when the Spanish left, the liberated Dutch adopted and continued the croquette-eating habit.

Finally, in the late 18th century, an Amsterdam publican named Jan Barentz noticed his customers were getting peckish while drinking, and were leaving to go eat elsewhere. In order to keep them boozing, he began selling small portions of cheese and sausage known as schnecks (from which derives the English term “snacks”). The story goes that Barentz’s wife created croquettes in bite-sized form to be sold alongside the cheese and sausage. Hence the bitterbal was born.

One thing bitterballen are not, however, is bitter. Their taste-deceiving name derives from the fact that spirits were their original dancing partners. Historically, the most popular, jenever (Dutch gin), was ordered as a bittertje, thus the snacks ordered alongside were (and still are) referred to as bittergarnituur: a “garnish for bitters.”

Bitterballen have remained a cornerstone of Dutch pub culture ever since. Nowadays they are almost always freshly deep-fried from frozen, heated to a temperature that could trigger a fusion reaction in a medium-sized star, then presented in a non-flammable dish to keep the server safe from spontaneous combustion.

The secret of eating bitterballen is not to dive in too quickly. Their thermonuclear heat means that any sensible person (or anyone with first-hand traumatic experience of failing to observe the rules), will set them to one side and attempt to ignore them for a good few minutes before tucking in.

Always let them cool to a level that can at least be measured on a normal temperature scale. Any temptation to dig in early risks a severe scalding and a possible trip to A&E. If you’ve ever woken up after a heavy night out with memory loss and blisters on the insides of your mouth, bitterballen could be the main suspect – for the latter at any rate.

Once cool enough to handle, they can be picked up with the fingers, dunked in the mustard that should have been served alongside (grain or Dijon by personal choice, although even the cheap luminous yellow stuff that comes from a tube will still cut through and balance the richness of the gloppy interior), then eaten with caution. But no double-dipping, please.

So what’s the enduring appeal of a dish that comes with such an element of risk? They are certainly hard to dislike. Nevertheless, if people were asked to name their favourite foods, it is probable that no one would mention bitterballen (and if anyone out there would care to contradict me on this, I will at least have the satisfaction of knowing someone has read this far).

On the face of it, who could blame people for not eulogising. A crispy if somewhat anonymous outer coating is a promising textural start, but bite into one and the amorphous, usually brown, sometimes yellow or even green sludge within doesn’t exactly tantalise the palate or inspire poetry. They are adequate and satisfying, yes. Even tasty on occasions. But rarely accused of being delicious.

One problem is that the quality of the filling can vary hugely from a slushy pile of unidentifiable putty to a satisfyingly firm mouthful of spiced and stewed beef (other foodstuffs are available). And there’s often no way of telling until the first bite.

On the other hand, a major factor in their favour is that they are simple to prepare. Provided the bar staff are smart enough to work a deep fat fryer without causing a kitchen fire and are passably conversant with operating a timer (or, as a fall-back, able to tell the time), you can’t go far wrong. No lengthy cookery courses to be followed, and the results are reliably consistent.

And nowadays, the choice of fillings on offer has expanded exponentially, from fish to mushrooms, especially as the hipster concept of “craft bitterballen” gains a foothold.

There will always be those who suggest bitterballen are at their best when served to any nearby wildlife (let’s say swans, to pluck a creature from the blue). Or when used in a game of tabletop pétanque. I am not one of those people.

So do I personally like these uniformly spherical micro-asteroids of mush? Well, I do have a soft spot for these original slimeballs. And they certainly become tastier the more beers you drink. But then, pretty much everything does.

In other words, “balls” to the naysayers. Ideally in portions of six or eight.